From the shadowy streets of noir to the complex panels of contemporary graphic novels, femme fatales have been a staple character in mystery storytelling. These dangerous women—seductive, cunning, and often deadly—have evolved significantly since their early appearances in mystery comics.

What began as one-dimensional stereotypes have developed into nuanced characters whose complexity reflects changing social attitudes and artistic approaches. This evolution tells us as much about shifting cultural perspectives on gender as it does about the development of comic storytelling itself.

The Classic Era: Post-War Noir Influences (1940s-1950s)

The femme fatale entered mystery comics primarily through the influence of film noir and hardboiled detective fiction that flourished in post-World War II America. These early comic incarnations borrowed heavily from their cinematic counterparts, both visually and thematically.

Visual Iconography: The Look of Danger

In series like “Crime SuspenStories” from EC Comics and “Crime Does Not Pay,” femme fatales were instantly recognizable through established visual shorthand:

- Deep red lipstick and perfectly styled hair

- Exaggerated hourglass figures and revealing clothing

- Cigarettes as props suggesting worldliness and moral ambiguity

- High-contrast lighting that often cast partial shadows across their faces

This visual language signaled to readers immediately that these women represented both desire and danger. Artists like Johnny Craig and Jack Kamen excelled at creating these iconic images that communicated volumes about character with a single panel.

Narrative Function: The Destroyer of Men

In these early mystery comics, the femme fatale served a straightforward narrative function: she was the beautiful trap for an otherwise “good” man. Her primary purpose was to tempt the protagonist (and by extension, the presumed male reader) while advancing a cautionary tale about the dangers of female sexuality.

Stories typically followed predictable arcs:

- A respectable man encounters a beautiful, seductive woman

- She persuades him to commit crimes or betray his principles

- She ultimately betrays him, leading to his downfall

- She either escapes punishment or meets a violent end herself

This narrative structure reinforced post-war anxieties about changing gender roles as women who had entered the workforce during wartime were being pressured to return to domestic spheres. The femme fatale represented fears about female independence and sexual agency outside male control.

Censorship and Adaptation

The implementation of the Comics Code Authority in 1954 severely restricted how femme fatales could be portrayed. Explicit sexuality, violence, and moral ambiguity—hallmarks of the classic femme fatale—were suddenly forbidden in mainstream comics.

Mystery comics adapted by:

- Softening femme fatales into “bad girls” who were redeemable

- Moving seduction to subtext rather than explicit content

- Ensuring these characters were always punished for their misdeeds

- Reducing their narrative significance and screen time

This censorship forced creative adaptation but also temporarily stunted the character archetype’s development in mainstream mystery comics.

The Transitional Period: Reinvention and Subversion (1960s-1980s)

As social attitudes shifted and the Comics Code gradually loosened, mystery comics began reexamining and reinventing the femme fatale in more complex ways.

The Anti-Heroine Emerges

The strict moral binaries of earlier decades gave way to more ambiguous characterizations. In series like “Deadly Hands of Kung Fu” and “Master of Kung Fu,” characters like Leiko Wu presented as femme fatale figures initially but revealed greater complexity and even heroic qualities as stories progressed.

These transitional femme fatales:

- Retained the visual signifiers of the classic femme fatale

- Initially appeared as threats or antagonists

- Revealed sympathetic motivations for their actions

- Often switched allegiances to assist the protagonist

- Maintained agency and independence regardless of their alignment

This evolution reflected the influence of second-wave feminism and changing perspectives on female characters in popular media.

Underground Comix and Breaking Boundaries

While mainstream comics were still restricted by the Comics Code, underground comix of the 1970s explored the femme fatale without constraints. Artists like Spain Rodriguez in “Trashman” and Howard Chaykin in early work like “The Scorpion” created femme fatales who were sexually explicit, unapologetically violent, and morally complex.

These underground versions introduced several innovations:

- Exploring female perspectives and motivations

- Connecting femme fatale behavior to legitimate grievances against patriarchal systems

- Using the archetype to critique social norms rather than reinforce them

- Experimenting with visual representations that challenged the male gaze

Though these comics had limited distribution, their influence gradually seeped into mainstream work, particularly as creators moved between underground and commercial publishing.

The Modern Reinvention: Complexity and Depth (1980s-2000s)

The 1980s marked a turning point for femme fatales in mystery comics, as greater creative freedom and maturing storytelling techniques allowed for more sophisticated character development.

Deconstructing the Archetype

Alan Moore’s “Watchmen” (1986-1987) offered a groundbreaking deconstruction of the femme fatale through the character of Silk Spectre (Laurie Juspeczyk). Initially presented with many visual cues of the femme fatale, Laurie’s character systematically undermines the archetype’s tropes:

- Her sexualized appearance is revealed as marketing imposed upon her by others

- She rejects manipulation as a power tactic in favor of direct confrontation

- Her relationships are complex and not primarily defined by seduction

- Her character arc involves rejecting the legacy of her mother (the original Silk Spectre), who more closely embodied the classic femme fatale

This deconstruction inspired other creators to examine what lay beneath the surface of the femme fatale archetype.

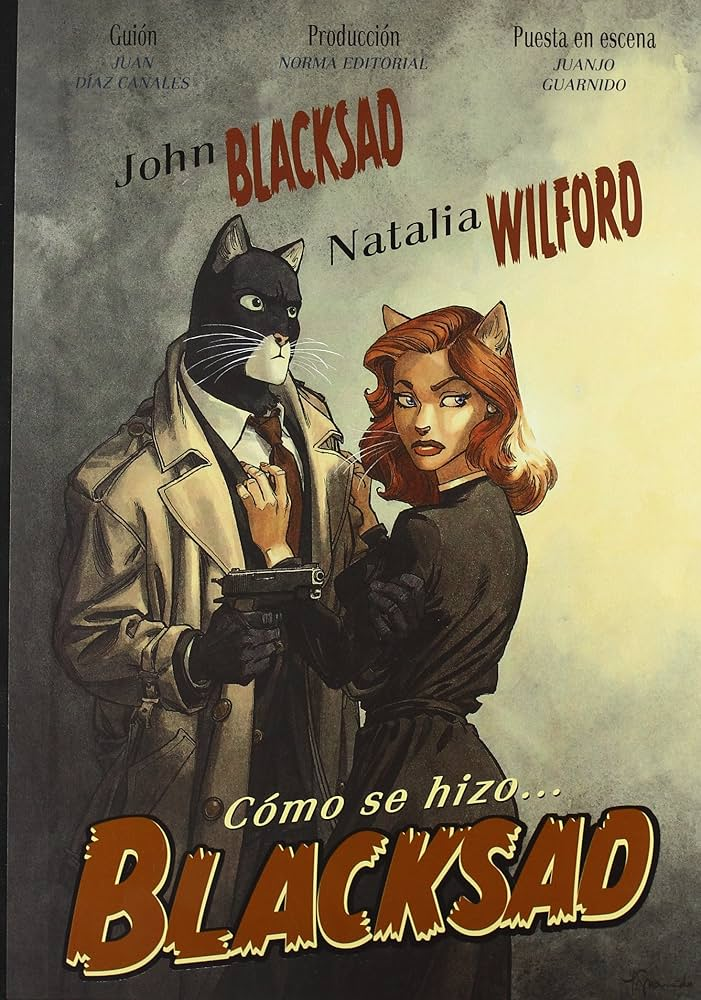

Noir Revival with a Twist

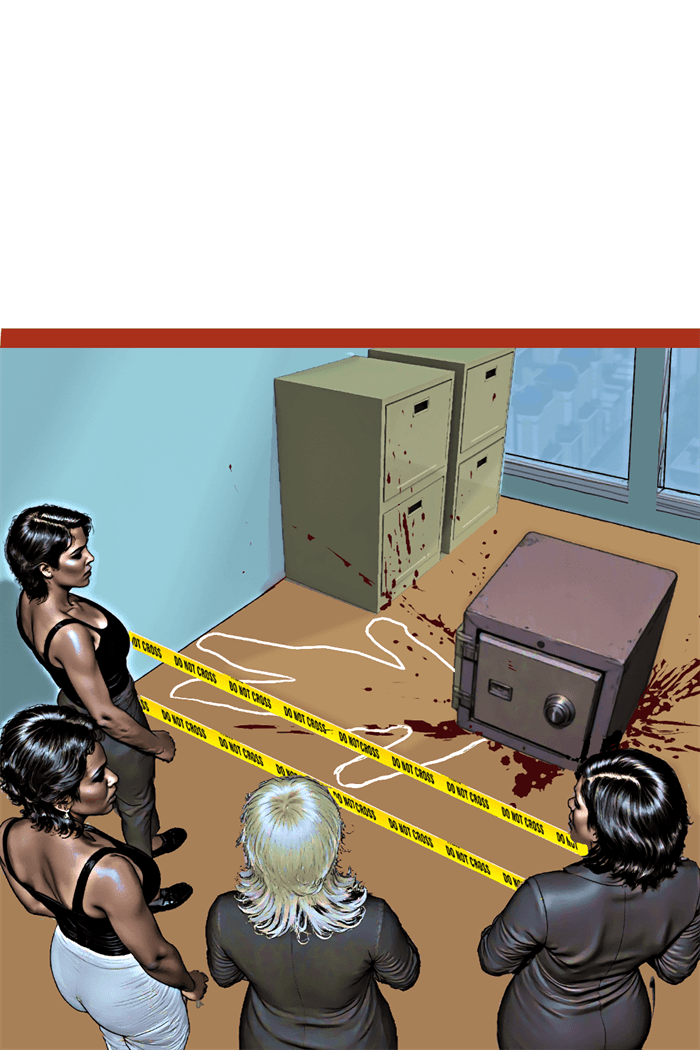

Frank Miller’s “Sin City” (1991-2000) revisited noir traditions but with significant revisions to the femme fatale concept. Characters like Gail and Miho in the Old Town sequence retained deadly and seductive qualities but operated within a community of women who used these traits strategically for collective protection and autonomy.

Miller maintained many visual elements of the classic femme fatale but subverted expectations by:

- Giving these characters clear moral codes and loyalty to their communities

- Portraying their deadly skills as professional rather than merely manipulative

- Allowing them victories rather than inevitable punishment

- Creating female networks rather than isolating these characters as singular threats

While Miller’s work has been criticized for other aspects of its gender politics, his reimagining of the femme fatale as part of a community rather than a lone predator represented a significant evolution.

The Femme Fatale as Protagonist

Perhaps the most significant development of this era was the shift from femme fatales as antagonists or supporting characters to protagonists in their own right. Greg Rucka and J.G. Jones’ “Whiteout” (1998) featured Carrie Stetko, a U.S. Marshal with a troubled past who incorporates elements of the femme fatale aesthetic while functioning as the detective protagonist.

Similarly, Ed Brubaker and Sean Phillips in “Criminal” created complex female characters like Greta who initially appear as classic femme fatales but are revealed to have depth, agency, and motivations far beyond their relationships with male characters.

These protagonist femme fatales:

- Maintained the dangerous competence of the archetype

- Used sexuality strategically rather than being defined by it

- Possessed complete narrative arcs independent of male characters

- Had morally ambiguous but comprehensible motivations

- Ended stories in ways other than punishment or redemption

Contemporary Approaches: Subversion and Diversity (2000s-Present)

The most recent era of mystery comics has approached the femme fatale with greater awareness of the archetype’s history and problematic aspects, creating deliberate subversions and diverse interpretations.

Role Reversals and Gender Fluidity

Modern mystery comics frequently play with gender expectations by creating male characters who embody traditional femme fatale characteristics or by introducing non-binary characters who utilize aspects of the archetype.

In series like “The Wicked + The Divine” by Kieron Gillen and Jamie McKelvie, characters across the gender spectrum employ seduction, manipulation, and deadly charm—traditional femme fatale traits—expanding the archetype beyond its gendered origins.

Terry Moore’s “Rachel Rising” features multiple female characters who embody different aspects of the femme fatale but in a narrative that centers female perspectives and relationships, effectively reclaiming the archetype from its origins in the male gaze.

Cultural Specificity and Diverse Representations

Contemporary mystery comics have also expanded the femme fatale beyond her traditionally white, Western incarnation. Series like “Fatale” by Brubaker and Phillips incorporate supernatural elements from various cultural traditions, while Brian K. Vaughan and Fiona Staples’ “Saga,” though not primarily a mystery, features femme fatale characters from diverse fantasy races and backgrounds.

Marjorie Liu and Sana Takeda’s “Monstress” draws on Asian mythology and aesthetic traditions to create femme fatale figures whose dangerous allure stems from cultural contexts beyond the Western noir tradition.

These culturally diverse femme fatales:

- Draw on visual traditions beyond Hollywood noir

- Incorporate mythological and folklore elements from various cultures

- Explore how beauty standards and seduction operate in different cultural contexts

- Connect feminine danger to specific historical and social circumstances

Meta-Commentary and Self-Awareness

Perhaps the most sophisticated contemporary approach involves femme fatale characters who demonstrate awareness of the archetype they embody. In Chelsea Cain and Kate Niemczyk’s “Mockingbird,” the protagonist Bobbi Morse occasionally performs femme fatale tropes with clear self-awareness, using cultural expectations strategically while maintaining her agency.

Similarly, in “Lady Killer” by Joëlle Jones and Jamie S. Rich, protagonist Josie Schuller—a 1960s housewife who moonlights as an assassin—consciously employs femme fatale visuals and behaviors as professional tools rather than innate qualities.

This meta-awareness:

- Acknowledges the constructed nature of the femme fatale archetype

- Uses familiarity with the trope for both comedy and commentary

- Allows characters to move in and out of the role as needed

- Distinguishes between performance and authentic character

Visual Evolution: From Object to Subject

The visual representation of femme fatales in mystery comics provides perhaps the clearest window into their evolution. This transformation can be traced through several key aspects:

The Gaze Perspective

Early femme fatales were invariably drawn from a male gaze perspective—presented as objects to be viewed rather than subjects with perspective. Contemporary artists have dramatically shifted this approach:

- Early era (1940s-1950s): Women posed to maximize sexual appeal regardless of narrative context

- Transitional era (1960s-1980s): More dynamic posing but still emphasizing physical attributes

- Modern era (1980s-2000s): Increasing focus on facial expressions and emotional states

- Contemporary era (2000s-present): Panels frequently drawn from the femme fatale’s perspective, making her the subject rather than object of the gaze

Body Diversity and Realism

The physical representation of femme fatales has also evolved significantly:

- Early era: Exaggerated hourglass figures with impossible proportions

- Transitional era: Slightly more realistic bodies but still idealized

- Modern era: Greater variation in body types though still trending toward conventional attractiveness

- Contemporary era: Genuine diversity in body representation, including age variation, different body types, and physical disabilities

Costume and Visual Signifiers

The visual shorthand that identifies a character as a femme fatale has expanded dramatically:

- Early era: Limited to tight dresses, lingerie, specific hairstyles, and red lips

- Transitional era: Beginning to incorporate diverse fashion while maintaining high glamour

- Modern era: Wider range of styles including professional clothing, practical attire, and period-specific fashion

- Contemporary era: Visual signifiers may be situational rather than constant, allowing characters to move between femme fatale signaling and other visual identities

Thematic Evolution: From Punishment to Empowerment

Perhaps the most significant evolution is in the thematic treatment of femme fatales and what they represent in mystery narratives:

Agency and Motivation

Early femme fatales were often portrayed as almost instinctively destructive, like forces of nature rather than rational actors:

- Early era: Motivated by greed, jealousy, or inherent evil

- Transitional era: Beginning to show realistic motivations like self-preservation

- Modern era: Complex motivations including principles, protection of others, and response to past trauma

- Contemporary era: Full psychological complexity with motivations that may be heroic, villainous, or ambiguous depending on perspective

Narrative Fate

The typical narrative conclusion for femme fatales has dramatically shifted:

- Early era: Almost always punished by death or imprisonment

- Transitional era: Occasionally redeemed through sacrifice or love

- Modern era: Varied fates including victory, compromise, or consequences proportional to actions

- Contemporary era: Outcomes based on narrative logic rather than moral judgment about female sexuality

Relationship to Other Women

Perhaps the most telling evolution is how femme fatales relate to other female characters:

- Early era: Usually isolated, often in competition with “good women”

- Transitional era: Beginning to show camaraderie with other morally ambiguous women

- Modern era: Capable of genuine friendship and loyalty to other women

- Contemporary era: Often part of female communities with complex internal relationships

Femme Fatales: The Dark Archetype Hiding in Plain Sight

The evolution of the femme fatale in mystery comics reflects broader social changes in how we understand gender, sexuality, and power. What began as a one-dimensional stereotype warning of the dangers of female sexuality has developed into a rich character type capable of carrying complex narratives.

Today’s mystery comics offer femme fatales who can be heroes or villains, protagonists or antagonists, but who are always fully realized characters rather than merely plot devices for male-centered stories. They retain the dangerous allure that defined the archetype but have gained the depth, agency, and complexity that transforms a stereotype into compelling character.

This evolution continues as contemporary creators—particularly women, LGBTQ+ individuals, and people of color—reclaim and reinvent the femme fatale from new perspectives. Rather than fading away as gender politics evolve, the femme fatale has proven remarkably adaptable, shedding problematic aspects while retaining the core appeal of a character who weaponizes expectations, embraces ambiguity, and refuses simple categorization.

In mystery comics, as in the best mystery stories, what appears simple on the surface reveals unexpected complexity when examined closely. The femme fatale’s journey from flat stereotype to rich character demonstrates how powerful archetypes don’t disappear as society evolves—they transform, revealing new facets and possibilities with each generation of storytellers.