When Noir Meets Neo-Future: European Creators Bring Fresh Perspective to Image Comics

Fans of innovative crime stories have a reason to celebrate this December. British creators Ram V, Dan Watters, and Laurence Campbell are set to re-release The One Hand & The Six Fingers, a neo-noir series that rewrites the rulebook with its dual-narrative format. The series is being offered in trade paperback in December. It’s good… very good.

This upcoming release underscores why Image Comics is synonymous with genre innovation. Since 1992, the publisher has cultivated a reputation for storytelling that defies convention, especially in crime and mystery. Titles like Powers (Brian Michael Bendis), Criminal (Ed Brubaker and Sean Phillips), and Thief of Thieves (Robert Kirkman) have expanded the boundaries of crime comics, exploring themes and structures often ignored in mainstream offerings.

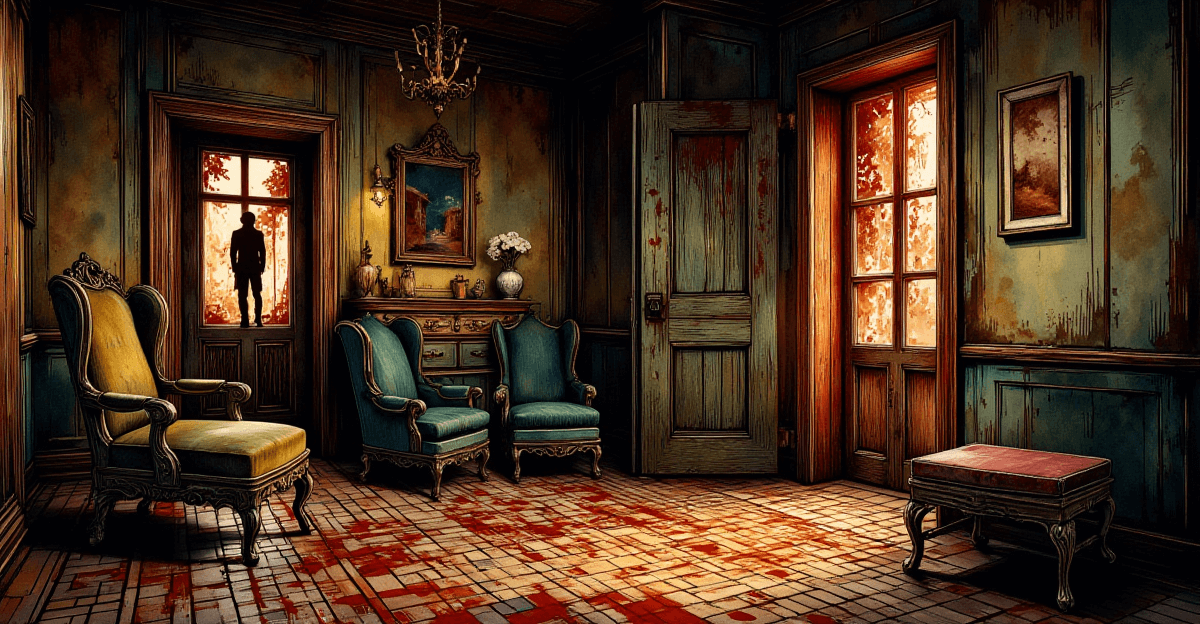

The genius of The One Hand & The Six Fingers lies in its dual approach. Ram V and Laurence Campbell’s storyline, The One Hand, follows a grizzled detective tackling an unsolvable case. Meanwhile, The Six Fingers by Dan Watters and Sumit Kumar tracks an archaeology student caught in a spiral of violence. Combined, these perspectives reveal a deeper narrative truth that, in Ram V’s words, emerges “in the spaces between.”

Laurence Campbell’s artwork reflects the moodiness and grit of his 2000 AD roots, while the layered plot pays homage to European crime fiction traditions. The London-based writing duo of Ram V and Watters channels their unique sensibilities into a vision of noir that feels global in scope but sharply personal in tone.

For Image Comics, this series is another notch in a belt already heavy with accolades for pushing artistic and narrative boundaries. The publisher has consistently proven that crime comics can serve as a canvas for profound, thought-provoking stories that resonate far beyond the typical whodunit.

Whether you’re drawn to noir’s shadowy streets or just looking for a gripping story, The One Hand & The Six Fingers is worth exploring. The trade paperback arrives in comic shops on December 11, with a wider release in bookstores on December 24.

Image Comics is Still an Industry Leader

Image Comics’ origin story is as audacious as the characters its founders once drew for the Big Two. In 1992, seven of Marvel’s biggest names walked away at the peak of their careers, armed with nothing but talent and a conviction that creators deserved control over their work. This wasn’t just a business decision—it was an artistic revolution. The fact is, the comics industry thrives on creativity and risks. Image Comics continues to lead the charge, championing creators and projects that remind us of what’s possible when storytelling has no limits.

Writing a comic book script is like playing chess against yourself—if you know the ending too soon, it takes the thrill out of the game. But when writing a mystery comic or graphic novel? You have to start with the crime. Reverse engineering becomes your best friend.

Writing a comic book script is like playing chess against yourself—if you know the ending too soon, it takes the thrill out of the game. But when writing a mystery comic or graphic novel? You have to start with the crime. Reverse engineering becomes your best friend.